What qualifications do you need to be a cartographer, a mapmaker?

Timothy Pont was a minister of religion. He lived in Scotland between approximately 1560 and 1627. He was the son of Catherine and Robert Pont, and his father was a Church of Scotland minister in Edinburgh who was also a judge (folk in those days knew as much about multi-tasking as crofters on Mull today). Timothy studied at St Andrews, then took several gap years – in fact he spent more than ten years in the 1580s and 90s travelling round Scotland. Travelling conditions would have been very different then. In 1601 he became minister of Dunnet Parish Church in Caithness, and left there in 1614, but his parishioners must have missed him in the pulpit for the whole of 1608 when he took a year’s leave ‘to map Scotland’. No small task!

He was the first person to produce a detailed map of Scotland. His maps are among the earliest surviving to show a European country in minute detail, from an actual survey. And he was the surveyor for them: a topographer. A man of parts.

Pont was also an accomplished mathematician. In connection with the project he made a complete survey of all the shires and islands of the kingdom, visiting remote districts, and making drawings on the spot. So he was an artist too, which was very useful in the days before photography. His ‘manuscript’ maps (that is ‘hand-drawn’) include thumbnail sketches of buildings like castles or abbeys. By now those buildings may be ruined, but Pont can give us a glimpse of what they looked like.

A contemporary described how Pont "personally surveyed...and added such cursory observations on the monuments of antiquity...as were proper for the furnishing out of future descriptions". He also used a whole range of symbols, which he called ‘characters’ – like the ones we are used to seeing on Ordinance Survey maps. But he was a pioneer. The originals of his maps are preserved in the National Museum of Scotland. We have a very helpful document: Guide to Symbols on Pont’s Manuscript Maps, from the Map Library there, showing how he recorded, as well as place names, natural and man-made features. The symbol for a mill looks like a hot-cross bun. I looked hopefully for Bunessan Mill, but of course it was built 150 years after Timothy Pont died, having almost completed his huge task of mapping Scotland.

James VI gave instructions that the manuscript maps should be purchased from Pont’s heirs and prepared for publication, but ‘on account of the disorders of the time they were nearly forgotten’.

In the end they were collated and revised by James Gordon, parson of Rothiemay (what is it about ministers and maps?) and they were published in Joan Blaeu's Atlas Novus, volume 5, Amsterdam, 1654.

Joan Blaeu, the atlas-maker, didn’t study Divinity, but law! He was born in 1596 in Alkmaar, the son of cartographer Willem Blaeu. In 1620 he became a Doctor of Law, but he then joined the family firm. Collecting, commissioning and publishing maps, they worked very hard and the world was their oyster. In 1635, they published the Atlas Novus (full title: Theatrum orbis terrarum, sive, Atlas novus) in two volumes.

You could also say that the sky was the limit, as in 1848 they published a world map Nova et Accuratissima Terrarum Orbis Tabula. This map was revolutionary because it depicted the solar system according to the theories of Nicolaus Copernicus, showing the earth revolving around the sun.... Although Copernicus's groundbreaking book On the Revolutions of the Spheres had been first printed in 1543, just over a century earlier, Blaeu was the first map-maker to incorporate this heliocentric theory.

Joan and his brother Cornelius took over the studio after their father died in 1638. Joan Blaeu lived on until 1673, and among other things became the official cartographer of the Dutch East India Company, a canny move.

From their printing presses came maps of Australasia and Dutch city plans, also a monumental French atlas in 12 volumes "En laquelle est exactement descritte la terre, la mer, et le ciel... With an exact depiction of earth, sea and sky".

But, more interesting to us, in 1654, Blaeu published the first atlas of Scotland, devised by Timothy Pont.

These atlases weren’t pocket-sized. They were designed for libraries in universities, merchants and trading companies, affluent patrons. Some were preserved with great care, as prestigious works of art. But of course, because they had a practical purpose, and exploration and colonialism and surveying skills kept moving on, some of these atlases were superseded, and in time were divided up into their individual pages.

That partly explains why, at the beginning of this year, the Historical Centre received an e-mail:

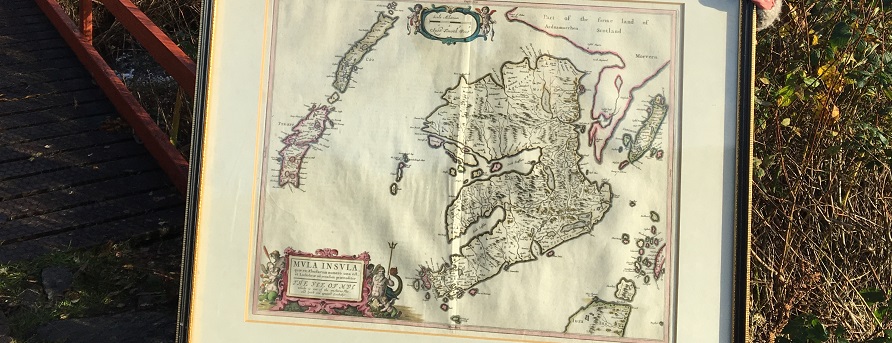

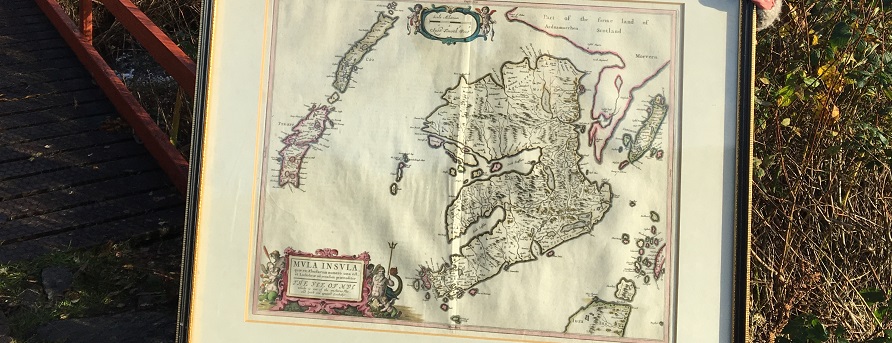

“I have a framed original Blaeu print of Timothy Pont’s ‘The Yle of Mul’ and wonder whether the Centre would like to have it.”

“Tell us more”, we said. And the would-be donor wrote:

“This is what I know about the Mull map. It was drawn by Timothy Pont around 1590 and after his death ended up with the Dutch printing firm Blaeu. I bought it in about 1962 as a manuscript from an Edinburgh bookseller and had it framed. It had come from an atlas of Scotland printed by Blaeu in 1654. Booksellers tended to break up the atlas to sell off the individual prints. You will see a crease in the middle of the map where it was folded into the atlas.

The back of the Blaeu maps had a description of the locality. I had the back of the map photographed and this is in an envelope attached to the map. At the time I got a translation from the old Dutch and this has gone missing. It may turn up when we move later this year. You could ask the Edinburgh Map Library if they have a translation or you could ask your Dutch neighbours if they could oblige!”

We said to the donor (who wants to remain anonymous) that we would be glad to receive the map. By a complicated journey and kindness of a neighbour, it was delivered from his home in Ardrishaig to a safe house on Mull, and now it is here......

But there was one more question, why did this person in Ardrishaig, who wasn’t a Member of the Historical Centre and had never lived in Mull, have the map? And this is the detail with which I’d like to end:

He wrote: “I came to Mull as a young engineer in 1959, working with the Argyll County Council team building the road from Fionnphort to the hill above Bunessan and surveying the road through the Glen. I had lodgings at Millbrae. After leaving Mull I lost touch with those I had known”.

So the map that he bought – because, like Timothy Pont he was a surveyor, and had come to know the Ross of Mull in great detail, and to appreciate it – has come back to Millbrae. It connects us with distant history and a wider world, and maybe helps us to see our place on the map.

Jan Sutch Pickard

The Ross of Mull is an extraordinary microcosm of all that draws visitors to the Hebridean Islands. The scenery, as you travel along the single-track road from the ferry at Craignure is breath-taking. You experience in the many walks in the area a true sense of wilderness; the secret bays with their beaches of silvery sand, the abundance of wildlife and the innumerable marks on the landscape of the lives of past generations and communities long gone. The Ross of Mull is a compelling place for anyone fascinated by history and the ancient way of life of the Gaelic people.