An sgeulachd mu linne a ’pheadair

The September issue of Round & About Mull & Iona carried a piece by Jack Degnan about 'The Pedlar’s Pool and Cairn' at Ardura, on the old road between the Ross and Craignure. In the same issue, Eleanor MacDougall wrote powerfully about ‘Fear and contagion in 1891’.

These two articles are re-printed here (plus the photo below), by kind permission of Janna Greenhalgh, editor of Round & About. They open up different aspects of the story of a man called Jack Jones and other ordinary people on this island, living through a stressful time. Some facts can be pinned down using our archives at the Historical Centre, but some of the – very moving – details vary. This often happens when a story is carried along by oral tradition – it grows or changes in the telling. What’s clear though, is that John Jones, whether a resident of Bunessan or a pedlar passing through, cared for victims of an epidemic at the cost of his own life. So, as the story was passed on, he became a local hero.

Since we shared this episode of local history with a local readership, more details are emerging. Apparently the death of John Jones was recorded in Torosay Parish - and there he was described as a resident of Bunessan. Eleanor says that she is continuing her research - so watch this space!

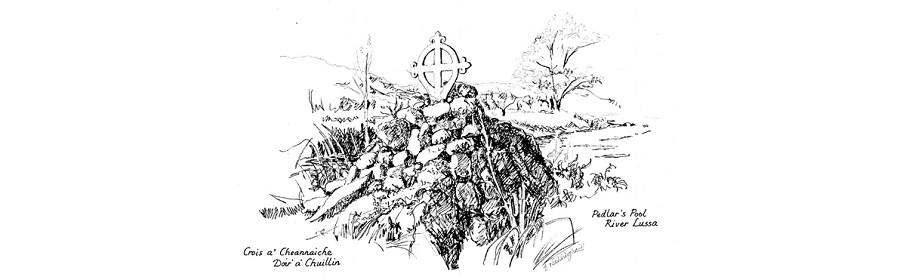

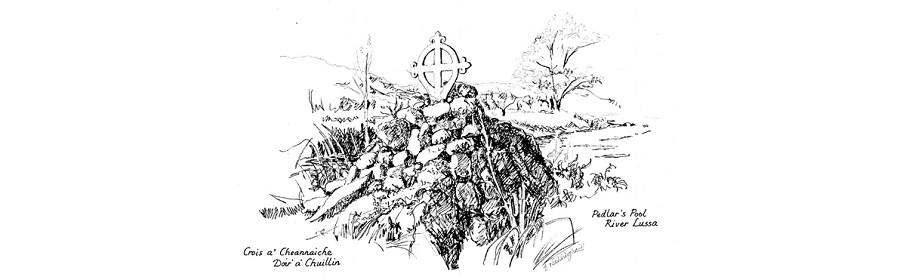

Eleanor also tells the story in Gaelic, which some readers may appreciate, and she made the beautiful line-drawing above.

Jan Sutch Pickard

A short drive from Craignure and about three quarters of mile along the old disused Glen More road beside the River Lussa from Strathcoil, in what is now the Ardura Community Woodland, can be found a small cairn surmounted by an iron Celtic cross with Fleur-de-lys emblems on three of the points of the cross. This is the Pedlar’s Pool and Cairn and the cross is inscribed ‘John Jones, died 1 April 1891, aged 60 years’. As well as being a lovely short, tranquil walk, the story has always interested me.

It is a sad tale of a man who is said to have lost his life helping and caring for others; a story that has much relevance to us in these times in which we now find ourselves.

As often is the case with such stories however, there are actually a few different versions of it. Peter MacNab in his ‘Mull and Iona Highways and Byways’ tells us that John Jones was a pedlar who, during his rounds, called at a house in the Ross of Mull where the occupants had been stricken down with smallpox. That disease was regarded then, according to MacNab: “with almost superstitious horror by the people, who would do little or nothing to help the victims. Food and drink would be left near the stricken house for the victims to collect, if they could.”

John Jones, it seems, was the only person prepared to nurse that family and look after the house. The fate of the family is unknown but this selfless act by the pedlar led to him contracting the disease and in due course, when Jones took to the road again, and arrived at this sheltered corner by the river, he died there.

Other stories have it that Jones supported a couple of families in Glen More who had been stricken with this terrible disease, staying in their cottages and looking after them and in so doing, contracted smallpox himself.

Hilary Peel in her book ‘Isles of Mull Iona and Staffa’ has it that the disease was typhus, an altogether very different disease from smallpox. Her version of the story has it that a Mr. Mitchell from Bunessan went to nurse a friend of his at Kinloch, Pennyghael and, in doing so, became ill himself and died at home. John Jones who, Peel tells us, lived in Bunessan, helped the doctor put the poor man into his coffin as everyone else was terrified of the illness. A day or two later Jones set out on his usual pedlar’s round through Glen More.

In the meantime, Mr. Mitchell’s married daughter who, along with her own daughter, had been helping to look after him in the last days of his life, persuaded Mrs. Mitchell to return to Glasgow with them. No-one would allow them in their boat as they were afraid of catching typhus so, against all medical advice, the three of them set out to walk the twenty-five miles (40km) to Craignure, hoping to get on a boat there. People in the houses of the Glen refused them shelter but left food out rather than take the travelers in.

That first night they slept out, huddled together, and the next day they overtook John Jones. At Craignure the Mitchell family were not allowed into the Inn but an old boat was upturned and made as comfortable a shelter as possible whilst they waited to take passage for Glasgow.

That same day the pedlar’s body was found in the Glen. Dr. MacCallum from Salen recorded on the death certificate that he had died from exposure. No mention of either smallpox or typhus.

MacNab and others, such as Peter Williams in his blogs, have it that the pedlar was buried on the spot along with his pack, and the cairn and cross erected some time later in his memory. I have been told by others however, that he is buried elsewhere but, so far, no-one has been able to tell me where.

Peel has it that money was collected for his widow, left alone in Bunessan and that years later this spot was selected to be called the ‘Pedlar’s Pool’ and a small cairn was erected in memory of ‘Jack Jones, the Pedlar’. I have also been informed that the folk in the Ross later felt so guilty and ashamed that they hadn’t followed the old Highland tradition of providing food and shelter, that they collected together enough money to provide both, not only the cairn and the cross, but also enough to provide a small pension for Jones’ widow.

I have tried to dig deeper into the story of John Jones to see if I could find the true story. For this I am grateful to the Ross of Mull Historical Centre who allowed me the use of their premises. It was here in the ‘Civil Registration Deaths Kilfinichen and Kilvickeon and Quoad Sacra Parish of Iona 1855-1955’ that I came upon the entry for the death of a Mr. Charles Mitchell, grocer, married to Agnes MacFarlane, who died of typhus on the 26th March, aged 62, at Bunessan. The date, place and cause of death would all seem to support Hilary Peel’s version of events. She has it that typhus came to Mull in the winter of 1890 and there are certainly records of death from typhus, such as that of John Campbell, a shepherd, aged 62, on 2nd December 1890 at Kinloch. There is an even earlier record of a death from typhus in Iona in 1861. However, there are also a number of entries of death from smallpox recorded in the late 1800s and early 1890s.

I should add that I could find no record for the death of John Jones in the register for the Bunessan area, nor that for his wife, so either they are recorded elsewhere which, for John, it would probably be the case as his death may have been recorded in Lochdon or in Aros, or else they may not actually have lived in Bunessan. Perhaps we will never know the true story … but if anyone out there can add to this, then I’d be delighted to hear from you.

I was talking, recently with Eilidh Young of Lochdon and she told me that the late Rev. Bill Pollock was obviously taken with this sad story of a man who gave his life for strangers and that, from time to time, he would walk to the cairn and lay flowers there and that he helped organise for the cross to be painted.

Jack Degnan

In early March 1891, a man from Gribun fell ill with typhus at Kinloch – the disease had already made an appearance among several Gribun families. No one at Kinloch was willing to nurse him for fear of catching the illness, and so the sanitary inspector asked a Bunessan man, Charles Mitchell, to attend to him. According to newspaper reports, Mitchell spent twelve days in Kinloch nursing the patient until he was well enough to go home. Mitchell then walked back to Bunessan. He had contracted the infection himself, however, and died at his home in the village on the 25th of March.

The people of Bunessan were terrified of typhus and for that reason, they refused to give any assistance to Mitchell's widow, Agnes. This left her in a predicament – she had no idea how she would coffin her husband's body or bury him. However, she did obtain help from the local doctor, and from a pedlar, John Jones, a man who regularly travelled through Mull and other islands, selling his wares. Charles Mitchell was buried in the graveyard at Kilpatrick, where his grave can be seen today.

Matters grew worse for Agnes after the burial because she couldn't obtain any services from local people. In addition, someone blocked her chimney with turf so that she couldn't light a fire. She had a nine year old granddaughter who lived with her, and when the child left the house to fetch water, neighbours threw stones at her. The persecution was such that Agnes decided to leave Mull and to take her granddaughter with her. On trying to board the steamer in Bunessan, however, the pair were denied passage by the crew. No one was willing to transport them across the island by vehicle, and so they were forced to walk through Glen More to Craignure, a distance of over thirty miles. News of Mitchell's death from typhus had gone ahead of them, and people who saw them coming along the road closed their doors or ran away. Thus Agnes and the girl spent two nights without protection in the Glen, in bitterly cold weather and sleet. Then, at a place called Craigmore, they came upon John Jones who was sheltering in a gravel pit beside the road – like the widow and her grandchild, he had been shunned by local people since Mitchell's burial. Agnes left Jones where he lay, because he was exhausted and unable to take another step.

In Craignure, Agnes couldn't get accommodation at the hotel or anywhere else – again, news of her husband's death had gone ahead of her. Eventually, with some help from the Salen doctor, she and her grandchild found shelter under a boat which lay on the shore. According to a story which came to me through my family (Agnes being my great-great-grandmother), she did receive food and a candle from a woman at Craignure Inn. It is said that she lit the candle and put it in her boot – and when she woke in the morning, the flame had burned a hole through the leather!

Two days later, Agnes and the little girl left Mull in a boat hired for them by their family, and went to Glasgow, where the widow had a married daughter. According to the papers, they were still weak and tired some days after their terrible ordeal. John Jones was less fortunate – he was found dead by a search party where Agnes had left him, and a grave was dug for him there. Inevitably, people feared that he had died from typhus – but the local doctor recorded his death as being from exposure.

Eleanor MacDougall

Tràth sa Mhàrt 1891, thàinig am fiabhras dubh air duine à Grìobainn a bha a' fuireach aig Ceann an Loch – bha an galar air nochdadh am measg theaghlaichean ann an Grìobainn mar-thà. Cha robh muinntir Cheann an Loch deònach altram a thoirt dhan duine air eagal gum faigheadh iad an tinneas bhuaithe. Mar sin, dh'iarr am maor-sitig air fear à Bun Easain, Teàrlach MacGilleMhìcheil, an duine bochd a fhrithealadh. A rèir aithrisean pàipeir-naidheachd, chuir Teàrlach seachad dà latha dheug ann an Ceann an Loch gus am b' urrainn dhan euslainteach dol dhachaigh. An uairsin, choisich Teàrlach air ais do Bhun Easain. Bha e fhèin air an galar fhaighinn, ge-tà, agus shiubhail e air 25 Màrt anns an taigh aige anns a' bhaile.

Bha eagal mòr mòr air muinntir Bhun Easain ron fhiabhras dhubh agus airson an adhbhair sin, cha robh iad airson cobhair a thoirt do bhantraich Theàrlaich, Aigneas. Dh'fhàg seo cùisean gu math doirbh dhi. Cha robh fhios aice ciamar a chuireadh i corp an duine aice ann an ciste, neo ciamar a thìodhlaicheadh i e. Co-dhiù, fhuair i cuideachadh bho dhotair na sgìre agus bho phacair, fear John Jones a bhiodh a' siubhal tro Mhuile agus eileanan eile a' giùlain stuth ri creic. Chaidh Teàrlach a thìodhlacadh anns a' chladh aig Cille Phàdraig far am faicear an uaigh aige fhathast san latha an-diugh.

Dh'fhàs cùisean fiù 's na bu mhiosa do dh'Aigneas an dèidh an tìodhlacaidh oir cha b' urrainn dhi seirbheis idir fhaighinn bho mhuinntir Bhun Easain. A bharrachd air sin, chuir cuideigin ploc ann an similear an taighe aice ach nach b' urrainn dhi teine a lasadh. Bha ogha aice a bha a' fuireach còmhla rithe – tè a bha naoi bliadhna a dh'aois – agus nuair a dh'fhàgadh a' chaileag seo an taigh gus uisge fhaighinn, thilgeadh daoine clachan oirre. Cho cruaidh 's a bha an geur-leanmhainn, chuir Aigneas roimhpe Eilean Mhuile fhàgail agus a h-ogha a thoirt leatha. Nuair a dh'fheuch an dithis ris a' bhàta-smùid fhaighinn aig cidhe Bhun Easain, ge-tà, dhiùlt an sgioba àite dhaibh. Cha robh duine sam bith deònach an toirt thar an eilein ann an carbad, agus mar sin b' fheudar dhaibh coiseachd tro Ghleann Mòr do Chreag an Iubhair, barrachd air 30 mìle air falbh. Bha daoine air cluinntinn mar-thà mu bhàs Theàrlaich bhon fhiabhras dhubh, agus nuair a chunnaic iad a' bhantrach agus a' chaileag air an rathad, dhùin feadhainn na dorsan aca agus ruith feadhainn eile air falbh. Mar sin, chaith Aigneas agus a h-ogha dà oidhche gun dìon anns a' Ghleann agus i fìor fhuar agus a' cur flin. An uairsin, aig àite ris an abradh Creag Mhòr, fhuair iad John Jones a bha ri fasgadh ann an sloc ri taobh an rathaid. Bha na h-aon duilgheadasan air a bhith aige – bha daoine air a sheachnadh bho àm tìodhlacadh Theàrlaich. Dh'fhàg Aigneas am pacair far an robh e, oir bha e gu tur claoidhte agus cha robh e comasach dha ceum eile a thoirt.

Ann an Creag an Iubhair, cha b' urrainn do dh'Aigneas aoigheachd fhaighinn aig an taigh-òsda air neo àite sam bith eile – a-rithist, bha daoine air cluinntinn mu bhàs an duine aice mus d' ràinig i. Mu dheireadh thall, le beagan cuideachaidh bho dhotair an t-Sailein, fhuair i agus a h-ogha fasgadh fo sheann bhàta a bha na laighe air an tràigh. A rèir sgeulachd a thàining thugam tron teaghlach agam (oir b' e seanmhair mo sheanmhar a bh' ann an Aigneas), fhuair iad biadh agus coinneal bhon òstair ann an Creag an Iubhair. Las Aigneas a' choinneal agus chuir i na bròig i – agus nuair a dhùisg i sa mhadainn, bha i air toll a losgadh tron leathar!

Dà latha an dèidh sin, dh'fhàg Aigneas agus a h-ogha Muile ann am bàta a chaidh fhastadh dhaibh le an teaghlach. Chaidh iad do Ghlaschu far an robh nighean aig a' bhantraich. A rèir nam pàipearan-naidheachd, bha an dithis aca fhathast lag sgìth seachdain an dèidh an turais uabhasaich. Cha robh John Jones cho fortanach – fhuaras e marbh ri taobh an rathaid do Chreag an Iubhair agus b' ann an sin a chaidh a thìodhlacadh. Gu do-sheachanta, bha eagal air daoine gun robh e air am fiabhras dubh fhaighinn – ach chlàr dotair na sgìre gum b' e buaidh na sìde a mharbh e.

Eleanor NicDhùghaill

The Ross of Mull is an extraordinary microcosm of all that draws visitors to the Hebridean Islands. The scenery, as you travel along the single-track road from the ferry at Craignure is breath-taking. You experience in the many walks in the area a true sense of wilderness; the secret bays with their beaches of silvery sand, the abundance of wildlife and the innumerable marks on the landscape of the lives of past generations and communities long gone. The Ross of Mull is a compelling place for anyone fascinated by history and the ancient way of life of the Gaelic people.